We got back from a fortnight in Belize on Sunday afternoon. It was, by my reckoning, the 38th country we’ve visited, on a trip we worked on with a well known UK long haul travel specialist. I say ‘we’: my wife did all the organising. I had almost no idea where I was going – this was a matter of choice, I hasten to add.

By the numbers:

– Photos taken: 580.

– Of which, keepers: 4.

– Wildlife encounters of the “you’ve got to be kidding” variety: 1.

– Arrests: 1.

A warning in advance: we had a scene play out on the way to the famous ATM Cave which was rather unsavoury, and which I can neither window dress [for reasons that will become very clear] nor skip, by virtue of being a significant talking point for a day or two for us. You might want to come back to this if you are having your lunch.

The default offering from the travel company is to fly in via Miami, which an overnight stay. That felt like a waste of time, so we asked if we could fly in via Mexico instead, as we’d be able to stay ‘air-side’ when we were transiting. This isn’t actually right, and made for a pretty tense return leg [which I’ll come back to]. Our agent also screwed up the booking and couldn’t get us on to the Cancun flight to Belize City, so we ended up having to stay in a Marriot just outside the airport anyway. This meant we’d have a pretty long drive to the Belize border on the first full day. In short, travelling via Mexico gained us nothing: if you’re thinking of travelling from the UK, just take the simple option and come in via Miami. Cancun airport is massive, and we had a chaotic 90 minute wait to get our bags. The refried beans we had at breakfast were fantastic but hardly enough to swing it.

We were dropped at the border and walked across the timezone [a first] and through passport control into Belize, sharing the queue with people who seemed to be taking little apart from vast quantities of toilet roll into the country. A short drive and boat journey later and we were at our first destination and highlight of the holiday, the Lamanai Outpost Lodge. Great food, lots of interesting things to do, great wildlife guides, and a really nice atmosphere: we couldn’t rate it highly enough. We were there for 3 nights, and had a nice mix of activities: a couple of wildlife spotting walks, a ‘village life’ tour [which involved making corn tortillas by hand. It’s pretty tough] and a standout ‘flashlight boat trip’.

As well as spotting a pretty interesting array of wildlife [including 3 metre crocodiles which, honest gov, don’t attack humans so feel free to take a dip in the river. Yeah right!], the guide used a laser pointer to talk us through various constellations. I’ve only ever seen the Milky Way as prominently once before and it was stunning: the guys turned the engine off, and left us floating in the middle of the estuary, with absolutely no visible sources of light to spoil the effect.

This little fella worked his / her way into our room, early in the morning of the second night, an encounter which had us carefully knocking out the contents of our walking boots for the rest of the trip.

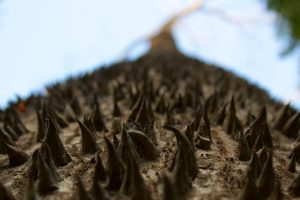

We had a really nice morning looking round the Mayan temples at Lamanai. The lodge had timed it that, apart from one other couple and their guide, we had the place to ourselves.

…which has been plastered over to protect the original stonework from the elements. My gripe is that it wasn’t done very sympathetically.

…something I gave up on later in the holiday.

Anything but the dreaded ‘…and what do you do…?’ Me, I like to judge people from a distance, without the whole palaver of having to find out what job they do first :).

…which I’ve completely failed to identify. We saw a few of these over the course of the stay:

This fella also put in an appearance on our second day:

What a fantastic name for a beastie!

We’d pre-booked a couple of trips and had the option for more, but I fell into my standard long haul holiday pattern of starting to feel off colour at the end of the first week, and had a couple of lazy days, including one where my wife went to the market at San Ignacio, which she enjoyed [possibly because she was on her own :)]. Our first big trip based out of Black Rock was to the ATM caves. It was a physically challenging, but fantastic day out. Right up until I saw the camera shaped hole in the skull of one of skeletons, I was grumbling under my breath about not being able to take my little sports camera [a GoPro wannabe, which I’ve got a waterproof enclosure for].

We had an interesting trip to the cave. We were travelling with the guide in a group of 6: a father and daughter, two women and ourselves. I was talking to one of the women who I thought was possibly drunk. Given that she was about 60, it was about 10 in the morning and we were about to ford a river, I thought she was pretty keen, but who knew, a little bit of Dutch courage might have been what she needed. We’d been walking for about 20 minutes, maybe half an hour, and were somewhere between the second and third river crossing when we noticed quite a distinctive smell. I, in my naivety, immediately thought that we might be passing near by some pecaris: our guide at Lamanai a few days before had pointed out that they have a pretty distinctive musky sort of smell. Looking back at this, I can just imagine my wife rolling her eyes at me; at the time I thought my jungle tracker super-skills had just landed. Anyway, about a minute later, we realised that the woman I thought had been drunk had suffered a spectacular sphincteral failure, and had pooed herself. Wearing shorts. In a group of people. Passing another group that happened to be heading to cave at the same time. And we’re not talking a little whoops-a-daisy squeak: there was poo running down the back of both of her legs to her feet.

It’s funny the way these scenes play out. Rather than sympathy, the group immediately regressed to the rules of the school playground. The only goal, and the one thing that was trying to jostle the smell from my brain, was the thought that we needed to cross the next river in front of her. The rest of the group was coming independently to the same conclusion and there was a not-quite-running foot race developing. Cue the Benny Hill music.

The woman cleaned herself up – probably launching an epidemic of dysentery in the otherwise crystal clear water of the river – and subsequently made it about 2/3 of the way through the cave – with no-one standing behind her at any point in time, I hasten to add.

So, as you might have guessed, my sympathy levels were pretty low. Yes, rather than drunk, she was probably medicating. But, what was she thinking? ‘I don’t feel well, but damn it, I’ve come all this way so I’m going to have a bash at this physically demanding day out.’ Or later: ‘OK, the gates have opened. Oops. I’m just going to try and brazen this bad boy out. Maybe no-one noticed’.

Really?!? I’m sorry, but either you don’t go – to the cave! – or, if it’s a super emergency, sprint off the path, drop your trollies and drop the kids. Fair enough, eye contact might be as light on the ground as waterproof toilet roll but people will understand: everyone has close shaves with the holiday trots. I remember one particularly tricky moment on my one and only diving holiday, struggling like mad to get out of a wet suit with the clock ticking down. But, back to the cave woman: to just try and walk it off? Or, if you are that ill in the first place?

Stay indoors. You know, next to the toilet.

The cave itself was, despite thoughts of poo-gate lingering over us like a green cloud, fantastic: just an absolute sensory overload of sights, swimming, sauna-like humidity and climbing. It’s not for the faint of heart.

We had another full day out to visit the ruins at Caracol. It was really good fun: a walk around the forest with the remains of houses and temples looming out of the undergrowth. We stopped off at a cave, called the Rio Frio, which was actually the highlight of the day for me.

We had one last mini-adventure to unfurl on the trip home. We’d arranged a pickup with the ground agent to get us to the airport a couple of hours before they had suggested, which turned out to be a good job. Our driver was stopped at a police check-point and told that his insurance had expired, which was an arrestable offence. His car would have to be impounded, he’d have a night in jail and could arrange bail for a release the next day. We were sat in the back of the car, thinking, yeah, shame, but we need to get to the airport pretty soon. The driver called his son and, after a testing 45 minutes wondering how reliable this arrangement was going to be, he appeared in a very fancy 4 wheel drive and took us to the airport at breakneck speed.

The airport at Belize City appears a little chaotic to the uninitiated: e.g., a mismatch on flight departure times between the main board and the gate, and a very strange seat allocation mechanism that seemed to involve a lot of shouting. Our flight was duly called and, when I realised there were only going to be 3 passengers, my hopes of a nice 737 started to evaporate. We were in a single engined plane for the 90 minute flight. Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the air pressure differential on the wing combined with thrust that was keeping the plane in level – and admittedly fairly smooth – flight, but an act of intense willpower on my behalf. I was a nervous wreck by the time we landed. My wife loved it. We landed at a small, separate terminal and, because our pilot and co-pilot accounted for exactly 40% of the people going through the place, cleared customs and immigration control in about 5 minutes. At Belize City airport, we’d arranged for a private taxi to take us to the main terminal for international flights – vastly overpriced [$35] but worth it to make sure we were in plenty of time for final leg of the journey home.

So, all in all, a very enjoyable trip. It has to be said, it was a quite expensive one. While some of that is down to currency exchange rates, it was principally because the accommodation was pretty dear. Bottom line, it was still one of the best holidays we’ve had. The people were really friendly, and the country itself has a great mixture of history, wildlife and beaches to offer.

Thoroughly recommended.

Photography Footnotes

I took my tripod but not my 16-35mm lens, which was a mistake. There are plenty of opportunities for taking shots of the Milky Way [something I’d never tried before], and missing a wide shot of the Rio Frio cave was a bit of a shame.

It’s also worth taking a shutter remote. I had a half-pissed brainwave to improvise by putting the camera on the B setting, and using the off/on to trigger the shutter by holding the shutter release button down by using a Neurofen and about 10 Band Aids [cue my wife rolling her eyes again.] It nearly worked, but I got a bit of movement in the camera body when I turned it on and off – a combination of a beer-induced unsteady hand, and setting the tripod up on less than solid ground.

Best of a bad lot, this was a 111 second exposure [I had a Band Aid failure which closed the shutter] at f4 and ISO 800. I also bounced the flash around the foreground. Going to f2.8 and wide on the 16-35mm would have just made the difference:

Stars – don’t look too closely…